The Last of Us Part II, Scar Island

For Blocktober 2021 I wanted to write about one of my favorite levels I got to work on for The Last of Us Part II: Scar Island.

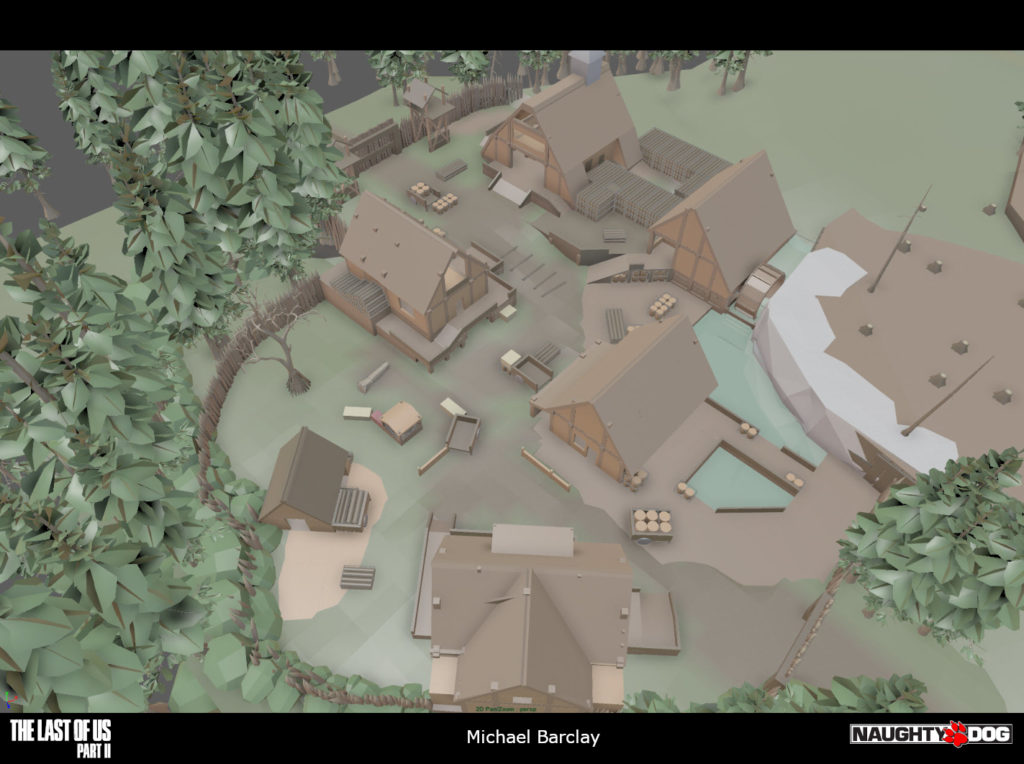

While “The Shortcut” was the first level I was officially assigned in The Last of Us Part II, the first actual work I did for the project was to build a little Scar Village prototype space. After we finished Uncharted: The Lost Legacy, our Director, Neil Druckmann, gave the team the pitch for the sequel to TLOU and I was immediately drawn to the presentation of the cult-like faction called The Seraphites, or “Scars” as they were also known.

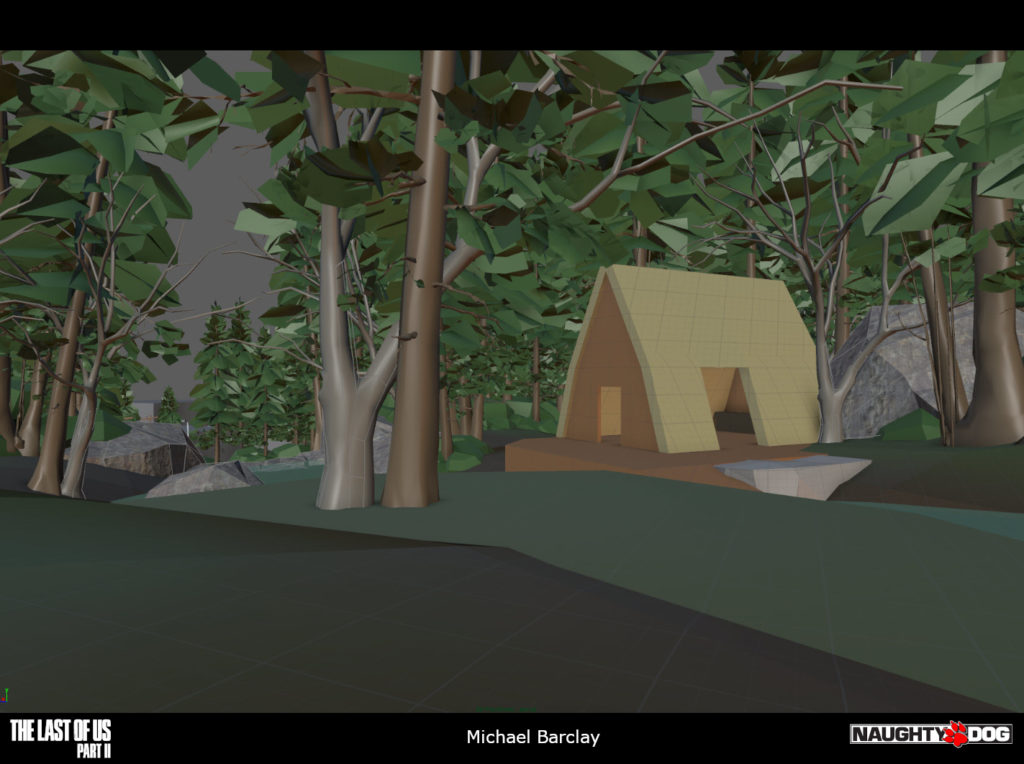

We had a bunch of amazing concepts for the Scars but no one as yet had tackled blocking out any of the structures that would become a core part of their identity: A-Frame shaped buildings that were built out of completely natural materials. The Scars live by a very strict code that prevents them from utilizing “old world” technology in their day to day lives. This means no electricity, no cars, fuel or anything of that sort.

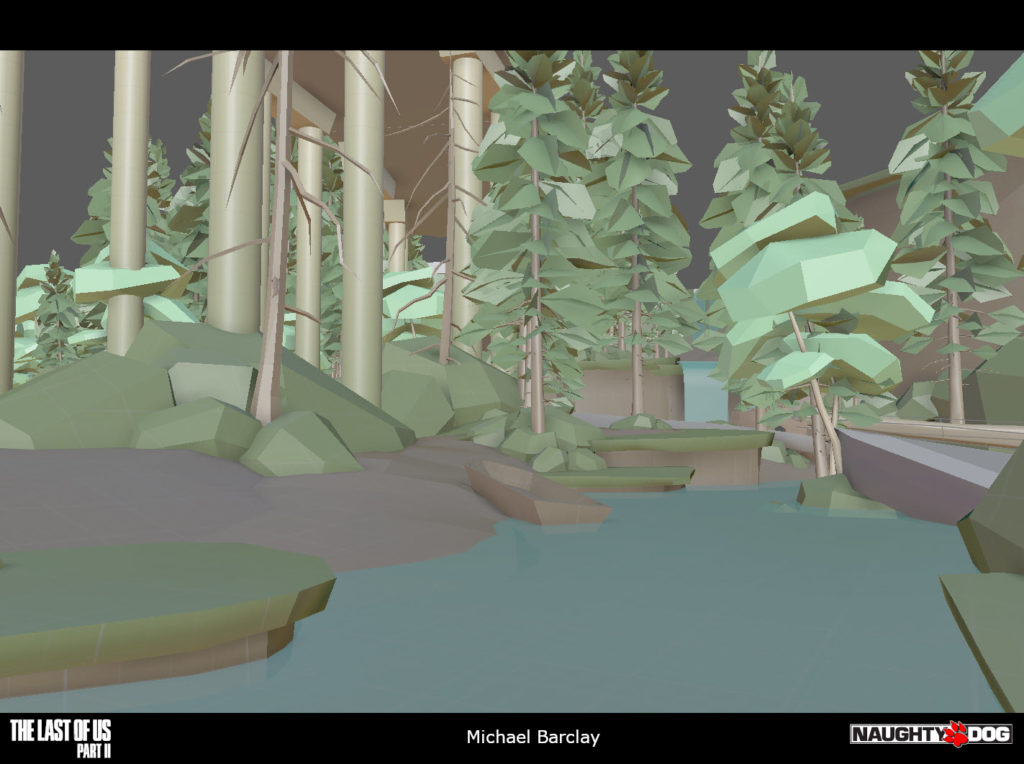

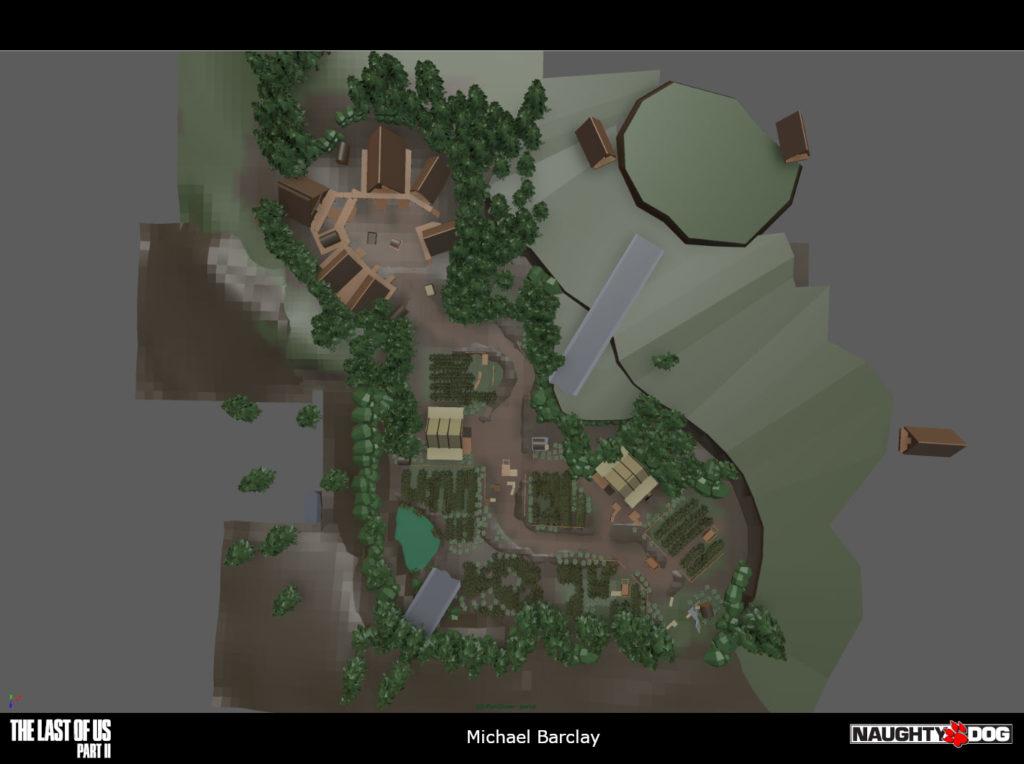

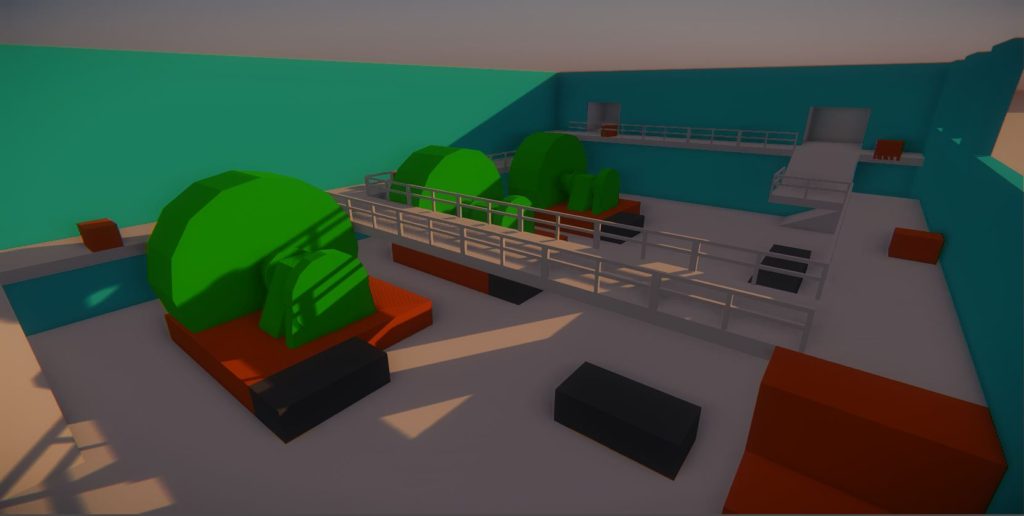

This was very exciting to me as it meant their home, which we decided would be an island protected from the ravages of the infected, would have the potential to be completely unique within the world of The Last of Us. While I was getting up to speed on the project I built a small combat space that would become a testing bed for many prototypes and developed shapes that I carried into many of my final blockouts. I wanted to build as natural an environment as possible to distinguish this level from others set in and around Seattle. You would see brief glimpses of the “old world” poking through the lush overgrowth that had swallowed the island, but for the most part this would feel like stepping into a completely new world.

Another goal for us within Scar Island was to present a different perspective of Scar culture and provide depth and texture to them as a faction. Throughout this level we see lots of examples of everyday Scar life, how they care for each other by hunting and cooking, where they pray and train as well as how they work since not all Scars are fighters.

It was very important to myself and the team that there were always opportunities for the player to avoid combat where possible and so all Scar encounters within this level can be completely “stealthed”. This meant very porous or wide encounter spaces, which actually helped maintain the aesthetic of broad, natural spaces.

One such encounter was known internally as “farmland”. I loved the idea of encountering Scars in a huge field of corn. A very simple layout with hardly any standard metrics for combat. I really enjoy breaking rules in layout where possible and trying new things, for The Last of Us an encounter where your main defense is vegetation was definitely unique. By swapping out hard cover for soft cover (a word we use for the practical use of vegetation in combat) across most of the space, it also helps to encourage a non-lethal or stealth style of gameplay. We still allow players who cannot help themselves but get into a fight to escape and reset combat, so it accommodates multiple styles of play.

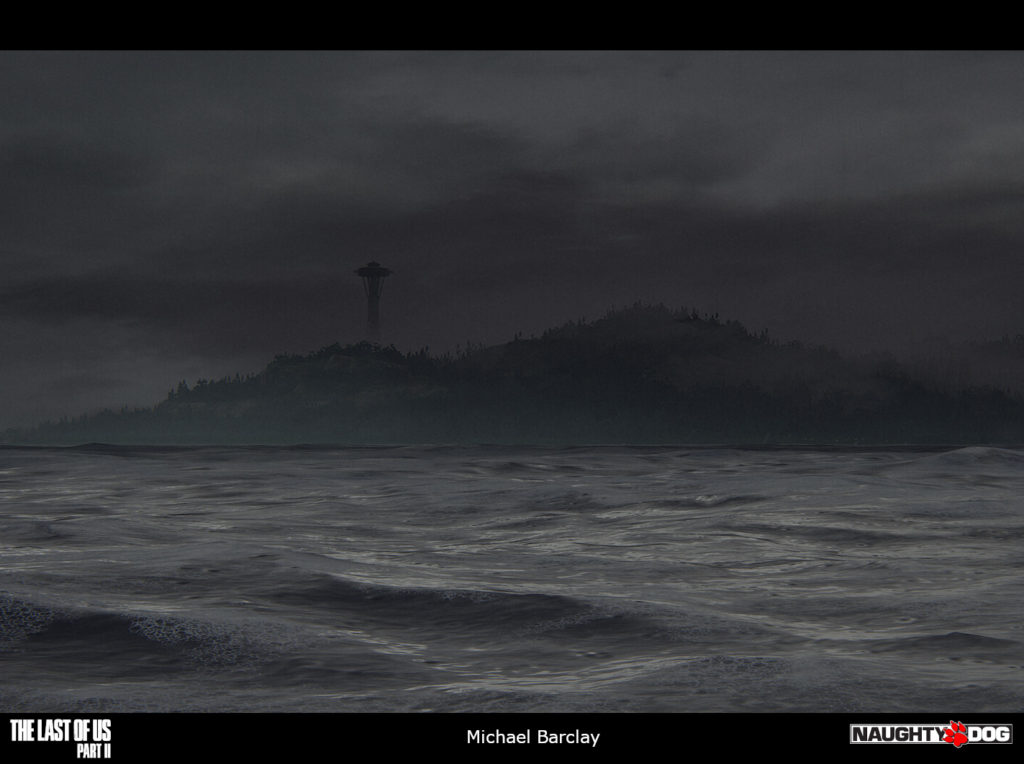

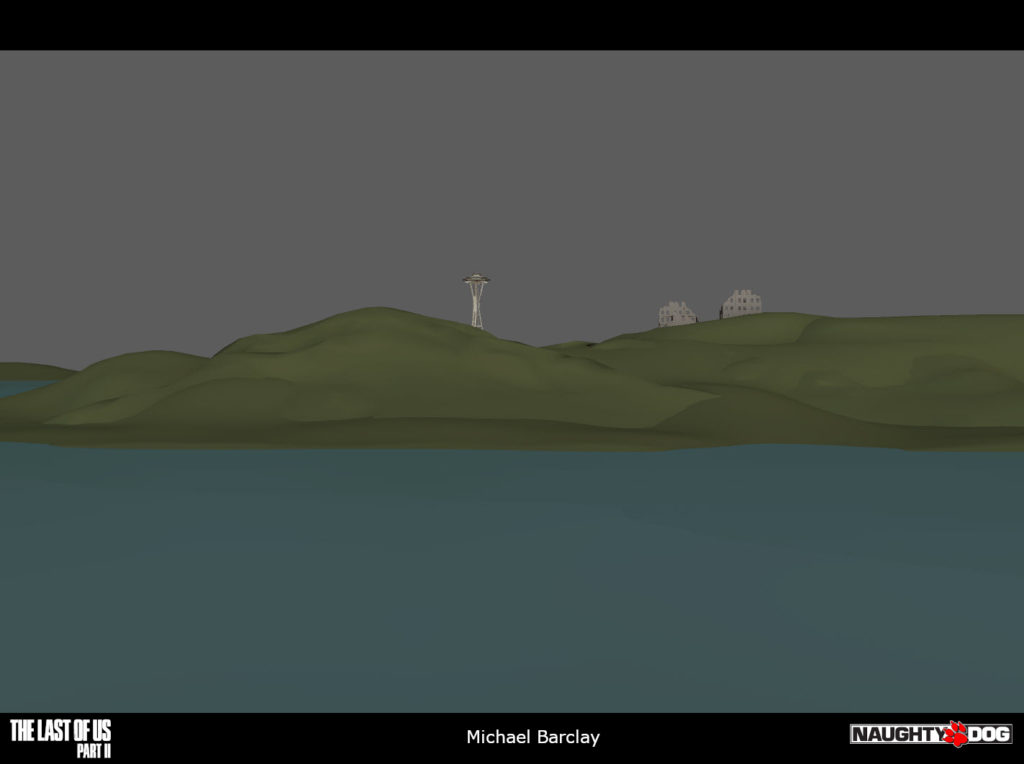

This is also one of the only places in the game that Seattle’s famous Space Needle is visible. I loved the idea that something so iconic could be lost in the forest of a new world where no one pays it much mind.

I was lucky to get to design Scar Island as a whole, from the moment Abby and Yara land on the shore to the point Abby and Lev boat away, and so I was able to personally oversee the level’s pacing in a way that we don’t always get to in levels that are bookended so closely by other spaces. To take advantage of this, I wanted to build Scar Island as seamlessly as possible. Since it was just me working on the space for so long, I’d be able to build a cohesive path through the island with no player-teleporting or fudging of spaces (which we often do in levels to keep landmarks visible or transition to new locations). The locations of all the important landmarks remain consistent throughout the level and I think it pays off by making the location and your journey through it feel more tangible.

The beats I was given for this level were “Abby and Yara go to Scar Island to locate Lev”, “Abby meets WLF”, “WLF kill Yara”, “Abby and Lev escape the island”. We knew that the initial experience of the level would focus on stealth and infiltration as Abby and Yara search for Lev. Once Lev has been located however I pitched several beats to the team that ramped up momentum towards the final escape such as a horse chase and sneaking through a logging camp.

We knew the back half of the level would have mixed combat encounters with both WLF and Scar factions fighting one another as WLF invade the island. There was a great opportunity here to show how Abby is primarily concerned for Lev’s safety and, again, combat is not something that needs to be entered until it’s absolutely necessary. I wanted to build spaces as wide as possible with very little verticality for this final escape. Emilia Schatz, who was co-lead designer for TLOUII, had prototyped a few spaces that we felt could work to that end. We took one of Emilia’s early layout prototypes as a basis for the encounter where Abby and Lev steal a horse while WLF and Scars battle one another. Once I added the space to the level I continued to modify and iterate on it with our amazing art and design teams until it became the version you see in the shipped game.

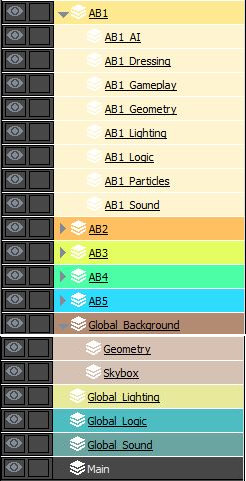

This process is becoming more common in AAA development and is sometimes known as “action blocking”. During pre-production a design team can produce dozens and dozens of prototype spaces in isolation. Some might already work with a level in mind, most however will teach us something about the game and will be thrown away. We had a bank of these encounter spaces that we often re-evaluated throughout production. If a level required a specific beat, we could save time and work by taking one of these “action block” spaces and re-purposing it. I recommend watching Respawn Entertainment’s Christopher Dionne discussing this process at GDC here.

I continued to pilfer our bank of action blocks when we needed an encounter space for Abby to face off against the WLF. Arnaldo Licea had a great space that showed a lot of potential in early prototyping. We took it as a basis for the new encounter space in Scar Island and worked with the concept and environment team to turn it into the brewery!

One of the biggest pitches I made to the team was to add a horse chase into the level. To me this allowed for a few benefits:

- I could frame Haven as very far away right at the start of the level and never have to cheat its position or teleport the player closer in order to preserve pacing since the horse would allow us to close loads of ground at the end in order to reach the capital.

- The horse chase would better sell the narrative and feeling of escaping and rushing towards a goal.

- The momentum of this set piece meant we were really ramping up the stakes as the level moved on.

I was lucky to get to work with Connor Brown, another game designer, on this setpiece as he came on to take over layout of this section part way through development while Karl Morley took on scripting duties. The final experience that Connor and Karl produced was one of our most iterated set pieces as there were multiple paths and beats to time out and everything had to be as fun as possible before passing off this really tricky space to environment art and effects.

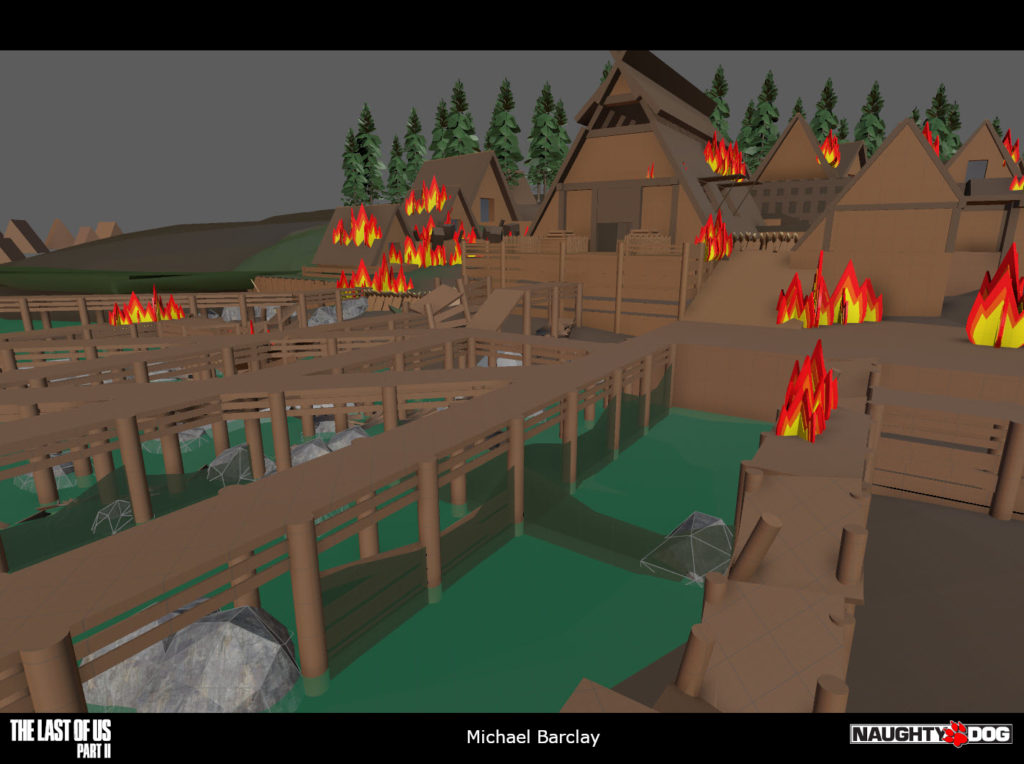

There were many significant challenges for this level and one of the largest was to pull off the amazing VFX you see near the end in the burning city. From the onset of production we knew the finale, the fight through the Seraphite capital “Haven”, would be set against a visual of raging fire as the WLF torch Scar buildings. To remind myself of this I added blockmesh fire to the level (to the amusement of the VFX team) but it was a good reminder that for most of this space, again, we were breaking rules and setting our regular level design shapes literally on fire. This means that cover and boundaries behaved differently here and it took a huge effort to get this playing right.

Overall Scar Island was one of the most enjoyable locations I got to design for The Last of Us Part II and I’ve been overwhelmed at the response it got from players. Hope any level designers out there also find something useful from the details of how it was designed.

Cheers!

_cover.jpg/revision/latest?cb=20150620153806)

I really like trains. Not in a parka-wearing, notebook-wielding kind of way, but in a “this is the best way to travel, specifically if I have to travel between Dundee and Manchester” kind of way. You see some excellent scenery and fascinating people. I once sat adjacent to a gentleman on a train travelling from Stockport to Edinburgh who had booked a table seat so he could watch Rab C. Nesbitt VHS taps on the Combo-TV/VCR he had brought with him. Even the tinny sounds of Gregor Fisher bellowing through the carriage couldn’t dampen my mood on a train. It helps that the UK countryside is a marvelous source of inspiration, if you get a chance to actually see it through the rain and fog and trips to the small kiosk next to the toilets for a £5 bag of crisps.

I really like trains. Not in a parka-wearing, notebook-wielding kind of way, but in a “this is the best way to travel, specifically if I have to travel between Dundee and Manchester” kind of way. You see some excellent scenery and fascinating people. I once sat adjacent to a gentleman on a train travelling from Stockport to Edinburgh who had booked a table seat so he could watch Rab C. Nesbitt VHS taps on the Combo-TV/VCR he had brought with him. Even the tinny sounds of Gregor Fisher bellowing through the carriage couldn’t dampen my mood on a train. It helps that the UK countryside is a marvelous source of inspiration, if you get a chance to actually see it through the rain and fog and trips to the small kiosk next to the toilets for a £5 bag of crisps.